Search This Supplers Products:Magnetic materials, magnetic equipment and devicesAuto Partstelecom devicesElectronicselectricalsmetals

magnetic saturation

time2020/08/27

- magnetic saturation

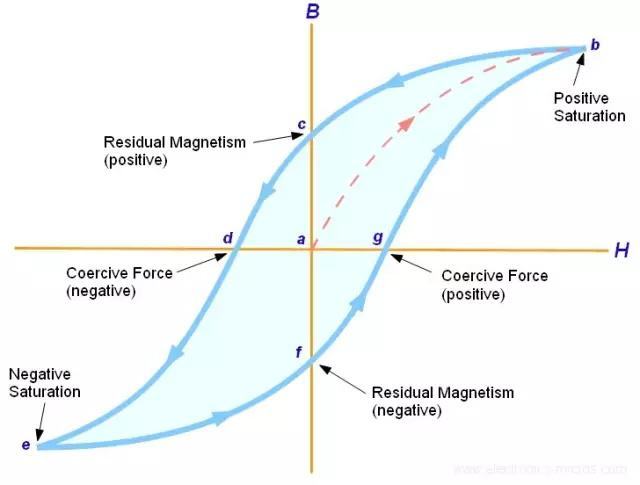

There are limits to how much induced magnetism is possible in different materials and similar workpieces of varying size, shape, and configuration. The principle of magnetic saturation observes that there is a point of diminishing returns at which attempting more externally applied magnetic field will give rise to no additional magnetic induction.

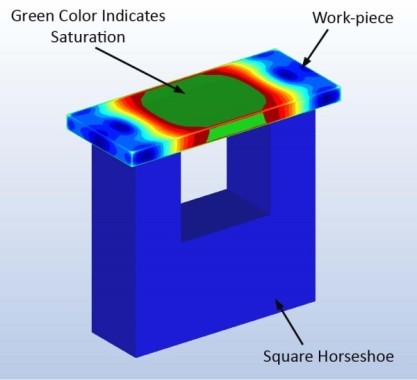

Increasing the thickness of a workpiece is generally beneficial. However, these changes will likely impact cost, mass, and possibly ease of manufacturing. It is therefore beneficial to understand and control for the magnetic saturation of materials during the design stage.

In conclusion:

- *Saturation can negatively impact a design by lowering the overall magnetic efficiency of the system.

- *Saturation of a material can be thought of the limit at which the material can carry magnetic flux. A pipe analogy works well as there is a limit to the volume of material carried by a pipe a there is a limit of magnet field a material can carry.

- *There is a limit to how much induced magnetism is possible in a material. When no more internal magnetism can be created within a material, it is said to be saturated.

- *Saturation is a fluid condition which is dependent upon the material’s magnetic characteristics and the intensity and direction of the applied magnetic field.

- *Thinner workpieces usually suffer from saturation more than thicker workpieces.

- Magnetic saturation in the workpiece limits the effective attractive force between the workpiece and a magnet.

Disclaimer: This post is for the free exchange of ideas and commentary regarding issues of interest to those in the field of magnetic or other industries. If the post infringes your legal rights, please contact us with proof of ownership, we will delete it in time.