Search This Supplers Products:Magnetic materials, magnetic equipment and devicesAuto Partstelecom devicesElectronicselectricalsmetals

Non-Conflict Mineral

publisherWilliam Chang

time2020/10/10

- VECTOR expects its suppliers to these aspects of its business to only source minerals from responsible sources and provide VECTOR with proper verification of the country of origin and source of the materials used in the products they supply to it.

What is Non-Conflict Mineral ?

“Conflict minerals,” as defined by the US legislation, currently include the metals tantalum, tin, tungsten and gold, which are the derivatives of the minerals cassiterite, columbite-tantalite and wolframite, respectively. Downstream companies often refer to the derivatives of these minerals as 3TG.

Conflict minerals can be extracted at many different locations around the world including the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The SEC rules define conflict minerals as 3TG metals, wherever extracted. For example, tin extracted in Canada, Russia or Argentina is considered a conflict mineral by definition. In the SEC rule, “DRC conflict-free” is defined as minerals that were extracted and did not directly or indirectly benefit armed groups in the covered countries. Therefore, tin extracted from Canada is considered “DRC conflict-free” under the definitions of the SEC rule.

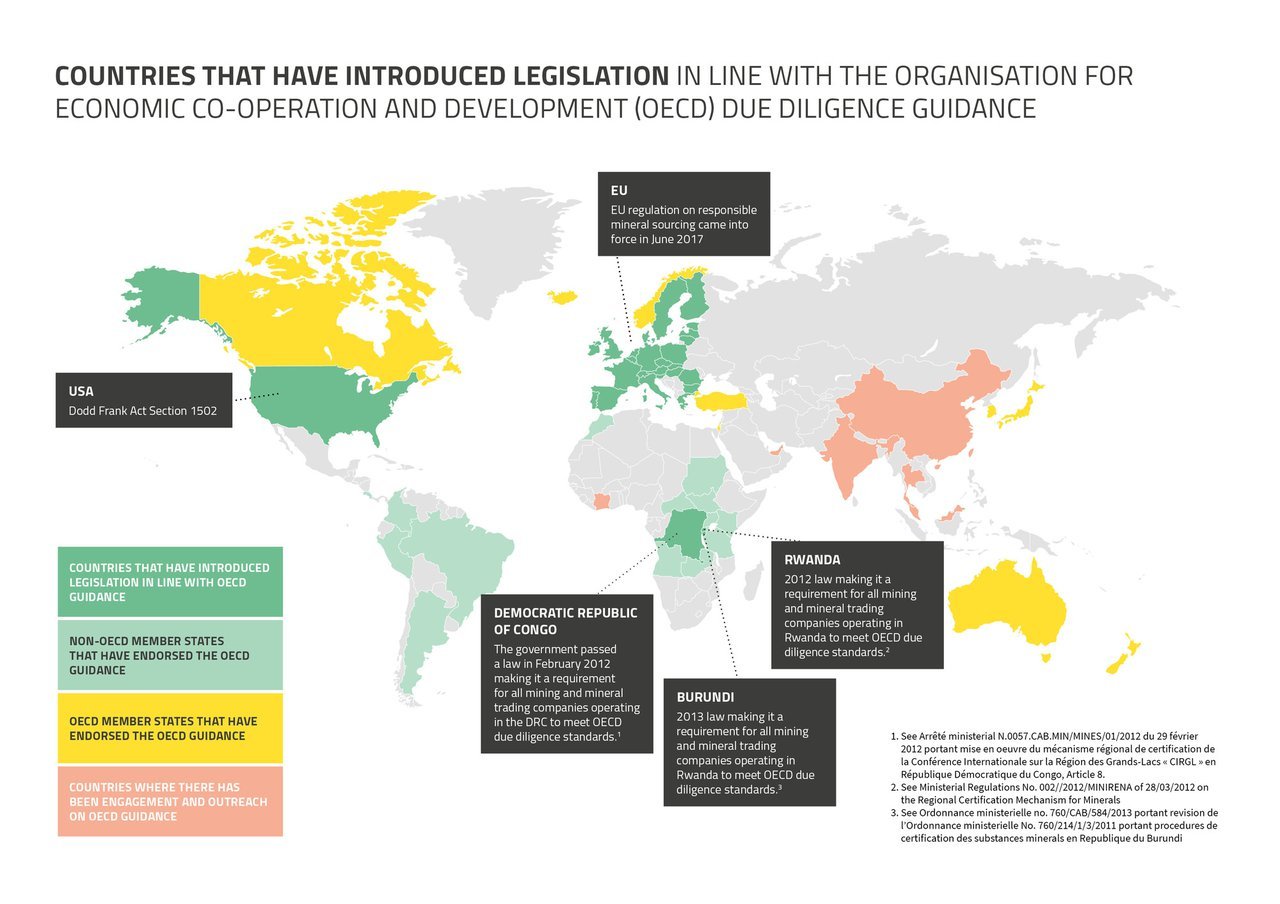

The internationally recognized OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas, has a broader scope and covers all minerals, not only 3TG.

Conflict resources in supply chains

Increases in business process outsourcing to globally dispersed production facilities means that social problems and human rights violations are no longer only an organization matter, but also often occur in companies’ supply chains, and challenge for supply chain managers. Besides the harm conflict minerals do where they are produced, human rights violations also raise an enormous risk to corporate reputations. Consumers, mass media and employees expect companies to behave responsibly and have become intolerant of those who don't.

Consequently, firms that are located downstream in the supply chain and that are more visible to stakeholders are particularly threatened by social supply chain problems. The recent debate concerning conflict minerals illustrates the importance of social and human rights issues in supply chain management practice as well as the emerging need to react to social conflicts. Conflict minerals are processed in many different components throughout various industries and hence have a high overall impact on business.

Initiatives like the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act or the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas demand that supply chain managers verify purchased goods as ‘‘conflict-free’’ or implement measures to better manage any inability to do so.

Minerals mined in Eastern Congo pass through the hands of numerous middlemen as they are shipped out of Congo, through neighboring countries such as Rwanda or Burundi, to East Asian processing plants. Because of this, the US Conflict Minerals Law applies to materials originating (or claimed to originate) from the DRC as well as the nine adjoining countries: Angola, Burundi, Central African Republic, Republic of Congo, Rwanda, South Sudan, Zimbabwe, Uganda, and Zambia.

Firms have begun to apply governance mechanisms to avoid adverse effects of conflict mineral sourcing. However, the mere transfer of responsibilities upstream in the supply chain apparently will not stop the trade with conflict minerals, notably due to two reasons:

On the one hand, globalization has created governance gaps in a sense that companies are able to abuse human rights without being sanctioned by independent third parties. This gap results in a non-allocation of responsibility that makes the problem of human rights abuses and social conflicts within dispersed supply chains very likely to endure, particularly without collaborative approaches to remedy these deficiencies.

On the other hand, conflict minerals usually originate from globally diverse deposits and are difficult to track within components and manufactured products. This is the case because they are mixed with minerals of different origin and added to metal alloys. Consequently, although the share of these minerals in single end products may be negligible, they are prevalent in numerous products and commodities. Together, these circumstances leave downstream firms nearly incapable of detecting risks associated with conflict minerals. Hence, the topic of conflict minerals becomes one of supply chain management rather than of individual companies’ legal or compliance divisions alone. What is needed is effective and supply-chain wide-mechanisms of traceability and due diligence that allow firms to take individual and collective responsibility as parts of supply chains.

In the context of mineral supply chains, due diligence represents a holistic concept that aims at providing a chain of custody tracking from mine to export at country level, regional tracking of mineral flows through the creation of a database on their purchases, independent audits on all actors in the supply chain, and a monitoring of the whole mineral chain by a mineral chain auditor. In this sense, due diligence transcends conventional risk management approaches that usually focus on the prevention of direct impacts on the core business activities of companies. Moreover, due diligence focuses on a maximum of transparency as an end itself while risk management is always directed towards the end of averting direct damages. However, besides the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act and the OECD Guidance, there is still a gap in due diligence practices as international norms are just emerging. Studies found that the motivation for supply chain due diligence as well as expected outcomes of these processes vary among firms. Furthermore, different barriers, drivers, and implementation patterns of supply chain due diligence have been identified in scholarly research.

VECTOR's Responsibility

As a global value-added manufacturer of magnetic materials, magnetic assemblies and magnet-related products, VECTOR promotes the traceability of these minerals and the transparency of the supply chain. VECTOR firmly believes that its customers should be fully informed about the products they purchase. While VECTOR, as a distributor, is not able to certify as to the country of origin of the minerals contained in the products manufactured by VECTOR's suppliers, VECTOR is committed to working with its customers to supply products that meet the customer's specifications.

With respect to those limited aspects of VECTOR's business that manufacture or contract to manufacture products that contain conflict minerals that are necessary to the functionality or production of the product, VECTOR does not directly purchase any conflict minerals from any source and endeavors not to purchase products that contain conflict minerals that directly or indirectly finance or benefit armed groups in the DRC or adjoining countries.

VECTOR expects its suppliers to these aspects of its business to only source minerals from responsible sources and provide VECTOR with proper verification of the country of origin and source of the materials used in the products they supply to it. VECTOR fully understands the importance of this issue to its customers and is committed to supply chain initiatives and overall corporate social responsibility and sustainability efforts that work towards a conflict-free supply chain. VECTOR is encouraging all of its suppliers to likewise support these efforts and make information on the origin of their product components easily accessible on their websites.